Key Points

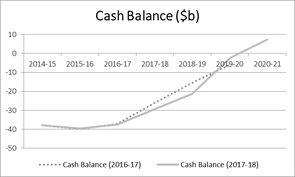

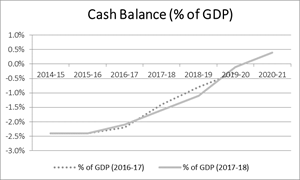

- The budget outcome in 2017-18 is expected to be a deficit of $29.4b in cash terms

- The 2017-18 Federal Budget forecasts a return to a small surplus ($7b or 0.4% of GDP) in 2020-21, with a budget deficit of $29.4b.

- This is without any expected sharp reduction in expenditure which has been a feature of previous returns to surplus.

- The political environment will act as a constraint on the Government’s ability to return the budget to surplus in the timetable outlined.

The Budget Result

The budget outcome in 2017-18 is expected to be a deficit of $29.4b in cash terms. This compares with:

- Previous year’s budget deficit of $37.6b

- The forecast of $26.1b in the 2016-17 budget.

While the deficit has fallen this year, it is higher than what was expected. In the context of fiscal management, it is behind where we were expecting it to be in terms of a return to surplus. However, the government is continuing to forecast a return to surplus in 2020-21.

In recent years, the way that fiscal policy has been reported has changed – the focus is no longer on the size of that year’s surplus or deficit, but on the long-term outcome – when the budget will return to surplus. This budget confirms what was promised in last year’s budget, but was outside the projection period and forecasts a small deficit ($2.5b) in 2019-20, and a return to surplus in 2020-21.

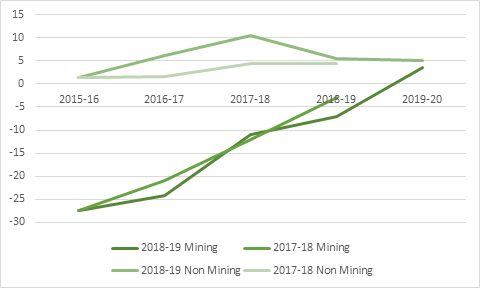

Figure 1: Budget Outcome

A comparison with last year’s budget shows that the deficits 2018-19 deficit is expected to be higher (that is, expenditure exceeding receipts by a greater margin), and roughly in line in 2019-20.

It should be noted that this is in the context of an economic environment which is no better than, and arguably weaker than, that envisaged in the 2016-17 budget. This is discussed in more detail below.

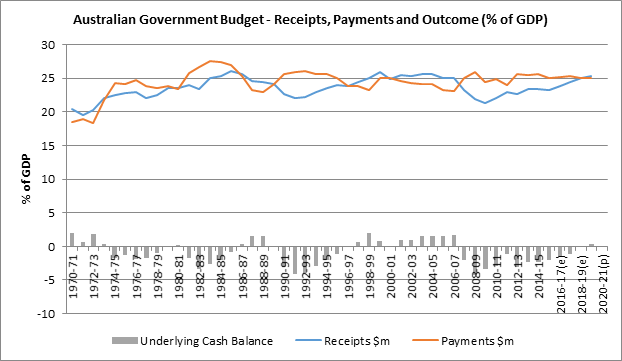

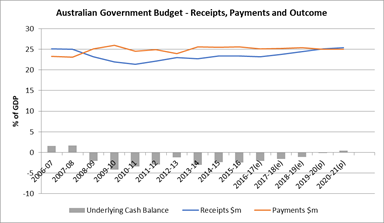

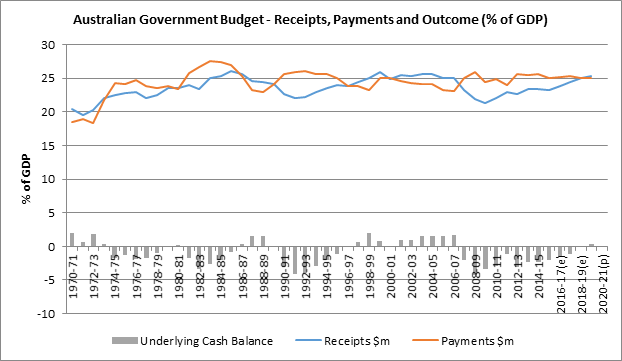

When we take a longer-term view, as in Figure 2, we can see that since 1970-71, the budget has returned to surplus on three occasions:

- 1981-82 for one year;

- 1987-88 through 1989-90; and

- 1997-98, following which it remained in surplus until 2008-09, with the exception of the year 2001-02.

Figure 2: Long term budget overview

It can be seen that each of these returns to surplus was accompanies by significant reductions in expenditure (or payments). If the forecasts in this Budget hold, this will be the first budget in 50 years to return to surplus without a significant reduction in Government expenditure in GDP terms.

The Economic Environment

As mentioned above, the improvements in the long-term budget outlook (from 2019-20 on) discussed above is in contrast to a generally weaker economic environment.

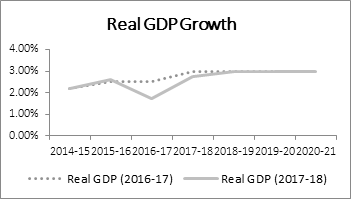

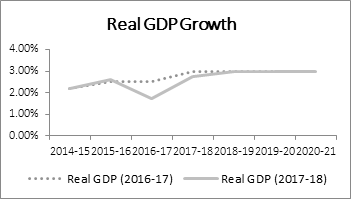

After achieving lower than expected economic growth in 2016-17, as shown in Figure 3, the forecasts in this budget revise the forecast GDP growth figures downwards until 2018-19. While this is reflected in the higher budget deficits in 2018-19.

After achieving lower than expected economic growth in 2016-17, as shown in Figure 3, the forecasts in this budget revise the forecast GDP growth figures downwards until 2018-19. While this is reflected in the higher budget deficits in 2018-19.

Figure 3: Real GDP Growth

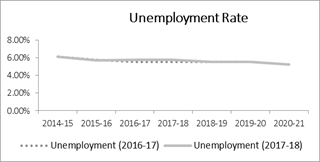

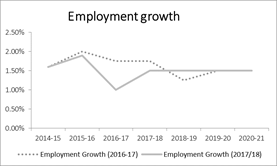

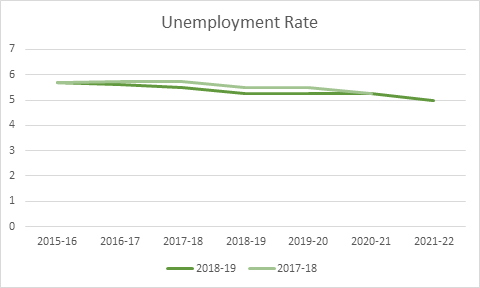

Unemployment forecasts (see Figure 3) remain relatively unchanged in this years budget compared with last year’s, with the slow, steady reduction in the unemployment rate repeated.

However, there unemployment rate in 2016-17 and 2017-18 is forecast to be 0.25 percentage points higher than those in last year’s budget.

When examined with the GDP growth assumptions in the budget, it can ve seen that from 2018-19 through 2020-21 feature cumulatively lower employment growth (meaning that the stock of labour available is lower) and constant GDP growth. This carries an implicit assumption about either an increase in the productivity of the Australian labour force or a change in the way that labour is allocated away from less efficient sectors.

Figure 4: Employment and Unemployment forecasts

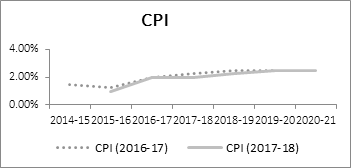

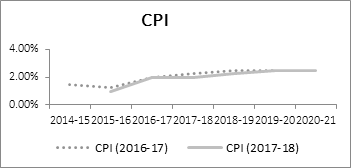

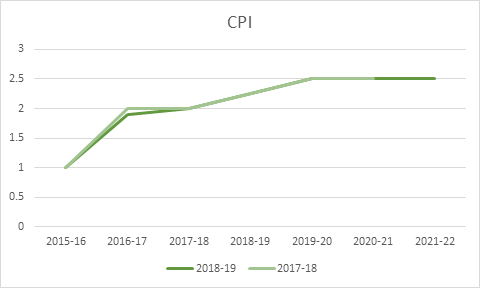

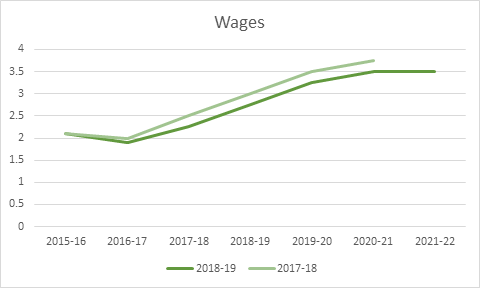

Inflation is forecast to remain at or below the middle of the RBA’s 2-3% comfort zone, suggesting little appetite for the central bank to increase Australia’s official interest rate. While this is a positive, such low inflation is typically associated with subdued economic growth. In relation to the Government’s previous budget, we note that inflation is expected to be lower than previously forecast.

Figure 5: CPI Outlook 2016-17 Budget -v- 2017-18 Budget

The Political Environment

In the absence of a strong economic outlook, the government will be required to finance the return to surplus through political capital. The increases in revenue which are designed to drive the return to surplus will be opposed by those who will face higher taxes, who it is assumed will be prepared to

However, there are limits on the Governments political capital, including:

- A one seat majority in the House of Representatives;

- Reliance on a diverse Senate, where it is required to negotiate with a range of minor parties with divergent interests and priorities;

- The Government and Prime Minister’s continued unpopularity;

- Competing, and even contradictory goals – measures which avoid short term hits to popularity are likely to impede the return to surplus which is increasingly being seen as a yardstick of economic management credentials.

Housing Affordability

In the period leading up to the budget, expectations were built around policies designed to improve housing affordability.

In broad terms, housing affordability is a difficult subject to address.

- Australian house sizes have been increasing – making like for like assumptions difficult. How does a 3 bedroom, 2 bathroom house common in the 1970’s compare with a 5 bedroom, 3 bathroom today?

- News stories featuring a charmless house achieving astronomical sales prices confuse the issue between housing affordability and land affordability. The houses acquired are typically destined for demolition and development.

The government has sought to address this by:

- Allowing first home buyers to use additional contributions to the Superannuation, attracting concessional tax treatment. However, this is limited to $30,000. While this may provide a first home owner with the ability to assemble a 5% deposit, it is unlikely that they will be able to achieve the 20% deposit which allows them to avoid Lenders Mortgage Insurance and the negotiating power with their banks arising from being less risky.

- Encouraging older homeowners to downsize by allowing them to contribute some proceeds from the sale of the principal home into superannuation without paying tax on the contribution, or it being counted towards any cap on contributions.

The Government has obviously matched these policies- increasing both the demand for property (from first home owners) and the supply of property.

The risk of this that it may create a shock to the housing market when, at the commencement of the second point, the pent up stock of housing may be released, putting sudden downward pressure on prices. However, when that stock is exhausted, prices will again rise.

Spending -v- Revenue

A frequent debate is whether Australia’s budget situation is caused by a problem with expenditure, revenue, or both. Looking at the summary of budget results in Figure 3, it can be seen that Commonwealth Government expenditure, has remained relatively static at around 25% of GDP

It can be seen that in 2007-08, coinciding with the Global Financial Crisis, expenditure rose and revenue fell in GDP terms. While

Figure 6: Budget Outcomes (GDP Share) 2006-07 to 2020-21

|

|

| |

Receipts

|

Expenditure

|

|

2006-07

|

25.1

|

23.3

|

|

2007-08

|

25

|

23.1

|

|

2008-09

|

23.2

|

25.1

|

|

2009-10

|

21.9

|

26

|

|

2010-11

|

21.4

|

24.5

|

|

2011-12

|

22.1

|

24.9

|

|

2012-13

|

23

|

24

|

|

2013-14

|

22.7

|

25.6

|

|

2014-15

|

23.4

|

25.5

|

|

2015-16

|

23.4

|

25.6

|

|

2016-17(e)

|

23.2

|

25.1

|

|

2017-18(e)

|

23.8

|

25.2

|

|

2018-19(e)

|

24.4

|

25.4

|

|

2019-20(p)

|

25.1

|

25

|

|

2020-21(p)

|

25.4

|

25

|

|

Election Timing

With a federal election due in 2019, if the forecasts described above play out, the government will either have delivered or be preparing a budget with a small deficit.

While this has obvious benefits in terms of evidence of an improving fiscal situation, this small surplus will mean that the government will have limited scope to engage in election promises in the short term.

After reducing government receipts (in GDP terms) in 2016-17, it will have increase revenue in the previous two years – every budget since the last election. If the budget has been delivered, there will have been a reduction in expenditure in GDP terms from 25.4% to 25%.

However, the Government is expecting to be experiencing stronger economic growth than any time since 2014-15, lower unemployment, and inflation within the RBA comfort zone, albeit slightly higher than in previous years.

Given that the economic forecasts for 2018-19 and 2019-20 are associated with significant uncertainty, and that the 2019-20 budget is likely to involve reductions in expenditure and increases in revenue, it is likely that the government will call an election before delivering the budget in May

After achieving lower than expected economic growth in 2016-17, as shown in Figure 3, the forecasts in this budget revise the forecast GDP growth figures downwards until 2018-19. While this is reflected in the higher budget deficits in 2018-19.

After achieving lower than expected economic growth in 2016-17, as shown in Figure 3, the forecasts in this budget revise the forecast GDP growth figures downwards until 2018-19. While this is reflected in the higher budget deficits in 2018-19.